This Weeks Case: Rob Zombie: Filmmaker or Film …Screw Up…Guy

Part 2: The Devil’s Rejects

Released: 2005

Written and Directed by: Rob Zombie

Starring: Sid Haig, Bill Moseley, Karen Black, and Sherri Moon Zombie

Synopsis:

In The Devil’s Rejects, police raid the house of the family Firefly only to be met with brutal resistance from members of the clan. The family flees and begins to make their way out of state, leaving a trail of carnage and bloodshed in their wake as all the while a vengeful local sheriff works tirelessly to hunt them down.

The Charges:

– Lacks a cohesive story

– Relentlessly violent

– Horrific disregard of any/all morals

– Soundtrack too predictable

The Defense:

I loved The Devil’s Rejects. As a film, it’s wonderful because it takes a character driven narrative that forces the viewer to confront an unflinchingly boundless variety of morbidity, perversion, and visceral carnage and then asks them to laugh at it, enjoy it, and leave the theater feeling thoroughly entertained and even (perhaps) a bit deliciously guilty. As a sequel, it ‘s wonderful because it uses the characters and the story from the first film to create a completely different and original experience.

Many people have said that The Devil’s Rejects is the film that House of 1000 Corpses should have been. This, to me, is an ingenuous statement. Half of the power of The Devil’s Rejects is supplied by the campy, over-referential nature of its predecessor. Even from the plain opening credits and straight-too-business beginning narration, it’s obvious that Rejects isn’t going to have the same sense of revelry and boundless theatricality that House so thoroughly embodied. While this all proves true, the plot of the film and the tone it presents belies a deep importance regarding the existence of the two films as equal halves of the whole story.

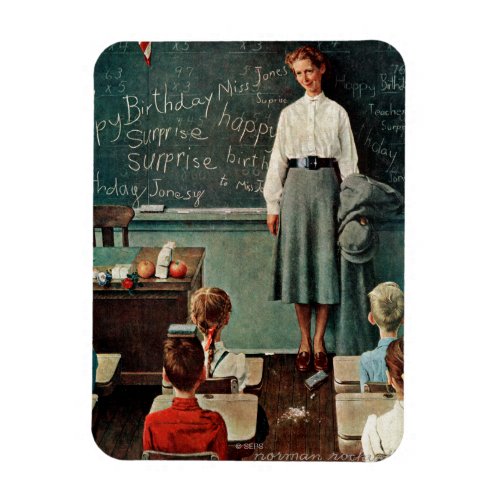

Simply put, House is told from the perspective of the victims and Rejects is told from the perspective of the victimizers. In House of 1000 Corpses, everything is going swimmingly for the bloodthirsty denizens of the titular abode. The show that the Firefly family puts on for the victims extends directly into the show that’s being put on for the audience via the film. It’s almost as if because we are seeing the Fireflies theatricality through the eyes of an other, the film takes on the same kind of guignol jocosity that the antagonists purvey as they set to their fiendish agenda. In Rejects, however, the Firefly Family is no longer performing. They are fending for their lives. This shift from the tone of House to the tone of Rejects is beautifully represented by the shedding of Captain Spaulding’s clown makeup and the change in motive from killing for fun to killing out of necessity.

That isn’t to say that Rejects isn’t funny. It’s very funny. All of the characters have retained their eccentric, perverse, and witty natures and Zombie’s writing is still as referential as ever. But the self-consciousness and sense of humor aren’t, as in House, demonstrated in the presentation. They’re demonstrated through character interaction, which, to the delight of all of Houses detractors, makes them far subtler. But, because of the POV shift in the film, this shouldn’t be viewed as an improvement over the other, but rather a necessary change. These aren’t references that are, for the most part, being made for fun. These are references being made out of necessity.

The Devil’s Rejects does not lack a cohesive story. It just doesn’t have a very complicated one. All of the depth and complexity of this film is built through the characters and not the actual series of events. Because the film doesn’t rely heavily on a start to end story concept, it allow for a more original product wherein references are easily swallowed as nothing more than references because the overlying events of the film don’t hinge on them.

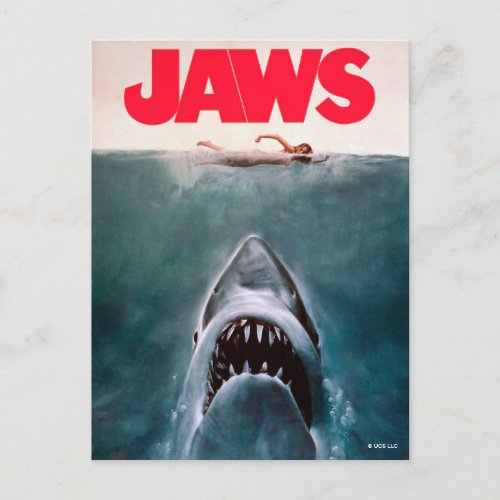

This film, like House, is very violent. In fact, it’s even more violent than House is. Not only are there more instances of graphically depicted deaths and abuses, the aforementioned drought of playfulness in the presentation makes the violence seem a lot more palpable and, in fact, real. While it seems cliché to argue violence as a means by which to challenge the viewer, this is exactly what Zombie is doing. Not, however, challenging viewers to find the own violence inside themselves or to see the truth about humanity and blah, blah, blah, but to witness the violence and then laugh at a pussy joke. Whereas House’s blatancy handed the humor and joviality to viewers in its theatrical presentation, Rejects dares viewers to find the humor for themselves. Because the film’s ultimately stoic tone doesn’t directly approve or disapprove of that laughter, it becomes a much more powerful experience of entertainment pared with an undeniable (yet, not wholly dissatisfying) sense of guilt.

The film’s complete lack of morals or even a single sympathetic leading character is yet another device used to make the audiences conversely light-hearted reaction to the film all the more important. Everyone feels safe laughing at a villain’s quips and victories when they know that, in the end, justice will inevitably prevail and the credits will roll only after a mandatory bout of impassioned face-sucking from the victorious protagonists. However, when the protagonists are the antagonists and the one would-be hero is admits to being just as sadistic and merciless as them, there’s no excuse for they’re laughter. Viewers can’t fall back on the excuse of our experiential knowledge that the heroes will prevail and so they’re forced to admit that they’re laughing because, for as sick and disturbing as the movie is, it’s fucking funny.

The predictable soundtrack just hammers this point home by giving the despicable villains the heroes’ music, just so the audience knows for sure that the whole business is totally intentional.

The Devil’s Rejects challenges viewers in a way that few film’s can and, in this way, proves Rob Zombie’s ability to make a film that isn’t just entertaining, but also relevant.

Written by Finley

![Cult Movie Queen Cheri Caffaro Publicity Photo [210906-0048]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2021/10/210906-0048-13x19-web-170x170.jpg)

![Harley Davidson Motorcycle 1993 Annual Report 2-Page Spread [I77]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2021/05/harley-davidson-annual-report-i77-01-170x170.jpg)

![Times Theatre (1940s) Times Square New York City Poster Photo Print [221230-9]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2023/08/221230-9-times-theatre-19x13-web-170x170.jpg)

![Charley Varrick Actress and Model Christina Hart Photo [221116-16]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2022/11/221116-16-christina-hart-85x11-web-170x170.jpg)

![Cult Flavor Print Series: General Doom Art Print [DP-221113-8]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2022/11/dp-221113-8-85x11-web-170x170.jpg)

![Claudia Jennings Gator Bait Publicity Photo [210906-0071]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2021/12/210906-0071-claudia-jennings-13x19-web-170x170.jpg)

![Shaun of the Dead 27×51 inch Licensed Beach Towel Simon Pegg, Edgar Wright [T54]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2022/04/t54-shaun-of-the-dead-movie-01-170x170.jpg)

![Pandorum Original 12×18 inch Promotional Movie Poster [I55]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2021/06/pandorum-i55-01-170x170.jpg)