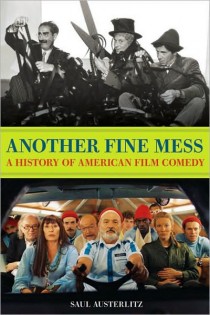

Another Fine Mess takes a thorough look at what the author calls “the bastard stepchild of American film… that [still] has one of the richest veins of American cinematic culture.”

To celebrate the release of Another Fine Mess, FilmFetish is giving away two copies of the book to readers.

PLEASE NOTE: To be considered to win this and all other contests, your eNews profile must be updated with your current mailing address, not just your email. CLICK HERE for further details and instructions on how update your existing profile, if necessary. Only eNews subscribers are eligible for contest prizes. Sign up for free RIGHT HERE.

In order to be entered into this random drawing for your free copy of Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy, you must also:

- Reply to this post and name your four favorite comedy films, from my list RIGHT HERE, and why you thought these films were so funny.

I’ll be running the Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy contest through Monday, September 13, 2010.

Through the Decades: Top 10 Great American Comedies

By Saul Austerlitz, author of Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy

Comedy is mostly without honor. Too often, comedy is treated as the bastard stepchild of American film. Rarely nominated for Academy Awards, or accorded the respect of a thoughtful newspaper review, comedies are considered the most disposable product of an industry dedicated to producing alluring but insubstantial goods. Drama, whatever its deficiencies, is granted the respect culture lends to noble intentions. Comedies, meanwhile, are seldom treated with the same deference.

And yet, comedy has always been one of the richest veins of American cinematic culture. Beginning with the silent era, when Charlie Chaplin was, for a time, the most recognizable face on Earth, comedy (alongside those other evergreen genres, the Western and the musical) has been what American films have done best. Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Ernst Lubitsch, Preston Sturges, the Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields, Mae West, Cary Grant, Billy Wilder, Jerry Lewis, Woody Allen, Robert Altman, Eddie Murphy, Albert Brooks, Ben Stiller – the list of standout comedic performers and directors overlaps with the list of exceptional American cinematic performers and directors, period.

Without further ado, then, here is a starter list of great American comedies – a sampler box of goodies, with one film chosen from each decade. It is hardly meant to be complete list of classics: for that, see my book Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy, which has my selection of the 100 greatest American comedies ever made. Instead, it is an introduction to that most underappreciated of genres – the comedy.

1. The Immigrant (Charlie Chaplin, 1917)

The Immigrant, the greatest of Chaplin’s shorts, is a film whose herky-jerky rhythms match those of the boat the Tramp takes to America: the Cy Young windup Chaplin uses to throw dice, the soup bowls skidding from one end of the dinner table to the other, serving two diners simultaneously, the alternation of whimsical and heartrending sequences. As a director, Chaplin nurtures an irony and delicacy that complement his balletic physicality and otherworldly grace as an actor. Chaplin was just beginning to experiment with films that were greater than the sum of their routines — an effort that would pay off with future masterpieces like The Gold Rush and City Lights. But if a comedy was more than just a comedy, could it still be funny? The answer was an unambiguous yes.

2. Sherlock, Jr. (Buster Keaton, 1924)

Sherlock Jr., Keaton’s funniest, and arguably his most accomplished, picture, was a master class in filmmaking doubling as a comedy. Walter Kerr described it as “simultaneously brilliant film comedy and brilliant film criticism.” Buster’s motion-picture projectionist dreams himself onto the big screen, emulating his favorite detectives while solving crimes with panache. The effect would be repeated numerous times by other filmmakers (most notably Woody Allen with The Purple Rose of Cairo), but Sherlock is uniquely consumed by the fundamental oddity of the motion picture as an art form.

3. Duck Soup (Leo McCarey, 1933)

Too quick for their dim-witted persecutors, the Marxes had unleashed a barely controlled chaos over the course of four films. They had yet to meet a foil agile enough to parry with them, or a director able to corral their energy. Leo McCarey and Duck Soup would change all that. It is the Marx Brothers’ masterpiece, and one of the small handful of undying works of comic genius produced by the American cinema. It channels their peculiar genius and mobilizes it for prescient, biting satire. Battling paper tigers no longer, Duck Soup finds the Marx Brothers unleashing the dogs of war.

4. The Shop Around the Corner (Ernst Lubitsch, 1940)

If aliens ever come to Earth and demand a fuller understanding of the moving pictures that seemed to occupy so much of our time in the 20th century, it would be best if we cut directly to the chase and screen the inimitable Ernst Lubitsch’s The Shop Around the Corner (1940) for them. The Shop Around the Corner is pure cinematic magic: the kind that, seen once, is indelibly burned into our brains, stored in the grottoes of recollection with the care and sentimental affection normally accorded only to our own fondest memories. The stupendous array of supporting characters in The Shop Around the Corner provide a milieu in which yearning lovers James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan insert themselves. The Shop Around the Corner is a melancholy romantic comedy that takes place on the brink of an abyss, and while Lubitsch is too much the comic raconteur to send his film over the edge, he pauses long enough for a sustained look. If you think you’ve seen this because you saw the Tom Hanks-Meg Ryan remake You’ve Got Mail, do yourself a favor and see the real thing.

5. Some Like it Hot (Billy Wilder, 1959)

Perhaps it makes the most sense to think of Joe and Jerry (Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon), the itinerant musicians of Some Like It Hot, as the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in a free replay of Howard Hawks’ Scarface. Adrift in a gangster epic not their own, these comic fools have been cut loose from their moorings, left to their own devices in a distinctly hostile world.A deliriously gender-bending exercise in over-the-top comic mania, Billy Wilder’s film features the best-ever performance from that underrated comedic master, Marilyn Monroe. Monroe sparkles as a romantic heroine with a self-deprecating streak, and Lemmon and Curtis are an ideal odd couple, years before Lemmon starred in The Odd Couple. “Nobody’s perfect,” as the film deliciously reminds us, but Some Like It Hot comes close.

6. Dr. Strangelove (Stanley Kubrick, 1964)

Dr. Strangelove is a Cold War comedy of frustration, whose scramble to avoid nuclear calamity is repeatedly spoiled by homegrown idiocy, knavery, and right-wing quackery — much of it in the form of star Peter Sellers, who plays three roles here. Director Stanley Kubrick once said of Strangelove star Peter Sellers, “There is no such person.” Seeing Dr. Strangelove, one begins to understand. Each character Sellers played bore so little relation to the others that it was nearly impossible to believe the same actor was behind them all. Possessed with a bursting enthusiasm for the glories of the post-apocalyptic, Sellers’ Dr. Strangelove is the dark angel of the mushroom cloud. Confined to a wheelchair, with an enormous upswept quiff of hair, and a single black glove, he is a lavishly ornamented peacock in a sea of buzzcuts.

7. Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1977)

Annie Hall (1977) had begun life as a loose-jointed mystery story before preview screenings decisively demonstrated that audiences preferred the relationship drama to the ostensible suspense plot. Even without the mystery story, Annie Hall is still two films in one: one a loose-jointed comedy in the vein of Allen’s earlier Sleeper, and the other a tender romance offering the first glimmers of Allen’s serious side. The looseness of Allen’s earlier work is unchanged, but the Marshall McLuhan cameos, animated sequences, flashbacks, and direct addresses to the camera are now all newly relevant, puzzle pieces for Annie Hall’s mixed-up jigsaw of human frailty. Annie Hall is one of the director’s funniest, and most touching, films, and the addition of Allen and Diane Keaton’s charming, messy, unsalvageable relationship to the template established by Bananas and Sleeper transforms Annie Hall into something entirely new for Allen: a somber comedy.

8. Lost in America (Albert Brooks, 1985)

The criminally underrated Albert Brooks takes that late 1960’s classic of rebel culture, Easy Rider, and turns it inside-out for the go-go 1980’s, crafting a parable of easily tempered yuppie rebellion. Distraught at the collapse of his ambitions — he’d picked out the new Mercedes and everything! — Brooks’ brittle yuppie convinces his wife to leave Los Angeles behind and explore the wide-open spaces of America. What they find is tragically, hilariously meager. The more delusional his characters, the happier Brooks is as a filmmaker.

9. The Big Lebowski (Joel Coen, 1998)

Looking for the missing trophy wife of a wheelchair-bound industrialist also named Lebowski, Jeff Bridges’ Dude encounters the Coen brothers’ broadest-ever array of screwballs and cranks: vaginally fixated performance artists, sex-offending bowlers, and wandering cowboys, drifted over from some other Wild West. The Big Lebowski is a wormhole down which one can disappear and never return. Lebowski is a marvel, being essentially a single, film-length shaggy-dog tale enclosed within an astonishingly tight script. The Big Lebowski is Raymond Chandler refracted through the perspective of a drug-addled hippie, The Long Goodbye if Elliott Gould’s Marlowe had chosen not to refrain from smoking a joint with his neighbors. The Dude abides.

10. Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy (Adam McKay, 2004)

Like Lebowski, another bottomless treasure-trove of quotable lines. Will Ferrell’s performance as a narcissistic San Diego newscaster is nothing short of brilliant, with notes of carefully honed self-absorption mingling with defensiveness, clumsy aggression, and a trace of wounded romanticism. Ron Burgundy is a marvelous caricature, half-cad and half-buffoon, the kind of guy who, when summoned onstage at a jazz club, professes surprise as he pulls a flute out of his jacket pocket. Ferrell is the ringmaster here for a glittering cast that includes Steve Carell, Paul Rudd, and Christina Applegate, his parody of oily self-assurance putting the entire film into air-quotes.

About the Author

Saul Austerlitz’s work has been published in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe, Slate, and other publications. He is the author of Money for Nothing: A History of the Music Video from the Beatles to the White Stripes and Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy.

![Psycho Actress Janet Leigh Photo [210906-98]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2024/04/210906-98-13x19-web-170x170.jpg)

![Sexy Cult Cinema Icon Sybil Danning Bikini Photo [221010-31]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2022/11/221010-31-sybil-danning-85x11-web-170x170.jpg)

![CBS Columbia Square Radio 1950’s Photo [221116-14]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2022/11/221116-14-11x85-web-170x170.jpg)

![Set of Two Original Photos: Air Force One and President Ronald Reagan [9111]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2019/10/ronald-reagan-9111-01-170x170.jpg)

![Star Wars: The Power of the Force Green Hologram Card Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew) Action Figure (1997) [1219]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2020/02/star-wars-chewbacca-1219-01-170x170.jpg)

![Death Wish II Actress Robin Sherwood Photo [221010-32]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2022/11/221010-32-robin-sherwood-85x11-web-170x170.jpg)

![Edward Scissorhands Movie (Johnny Depp) 27×51 Licensed Beach Towel [K32]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2023/01/P1470911--170x170.jpg)

![Hal Holbrook Mark Twain Tonight + More of… Volume II Set of Both Vinyl Editions [U26]](https://www.filmfetish.com/img/p/2021/07/mark-twain-tonight-set-u26-01-170x170.jpg)